Group Negotiations

Advice on how to tackle the issues and get an agreement with a business group negotiations.

When you have a group of managers sitting in a boardroom, you could be reminded of ancient Roman days, when two or more robed members, clustered in the shadows intent on forming a power block. Plotting to cause the downfall of another member or leader. Being a Caesar or a Senator of the ruling class in Roman times, often meant a very limited life span. It was not always the greatest gig it might have seemed on the surface.

At times modern budget meetings don’t seem all that dissimilar, minus the assassinations and the messy bloodshed. Yet nonetheless, group negotiations can consist of self-serving interests that run contrary, to the good of the organization as a whole. Coalitions might form to the detriment of the organization. Even though a group of people might seemingly be working for a common cause, their underlying interests might run contrary to the common good. These problems should not be seen as obstacles, but rather as challenges that have to be overcome.

Resource allocation amongst groups

Be careful about making assumptions about the groups with whom you are negotiating. A group or team of colleagues sitting at the table might be collectively, either a cooperative group, or a competitive group. Jumping to a conclusion that one represented group, might automatically be considered either adversarial or cooperative, might result in the wrong mindset.

Generally speaking, most represented groups within this potentially complex mosaic, are likely to contain a mixture of both cooperative and competitive interests. They might seek to cooperate on some issues in an integrative framework, or seek to grab as much as they can, in an altogether different distributive framework. Their attitude will likely depend on the particular issues being discussed or negotiated.

The more diverse the group sitting at the table, the more likely you will face multiple interests, positions, and perceptions of what’s fair, and how to reach or make decisions. The best means to achieve harmony and maintain group cohesion, is to agree about how the resource allocation will be divided amongst the group representatives – who’s going to get what.

There are several choices you can employ as a group, to smooth the progress of an agreement. The equity allocation rule, divides the total amount of the available resources, then distributes them in proportion to each group’s input to the negotiations.

There is also the equality rule.This rule divides the resources equally amongst the representative groups. To do this successfully, we need to know the preferences of all the representative groups involved. Otherwise, the alternative is that each group will make an effort, to follow the means that most benefits their own position.

Making negotiation rules and determining agendas

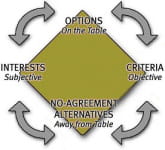

There are several things that a group must determine if they are to make successful decisions. As there are many motives for entering into a negotiation, Bazerman and Neale, authors of ‘Negotiating Rationally‘ have suggested the following criteria, to evaluate the quality of the mixed-motive negotiation.

- Does the group expand its focus to include all viable negotiable issues in the discussions?

- Does the group discuss priorities and preferences among issues?

- Does the group focus its efforts on problem solving?

- Will the group consider unique and innovative solutions?

- Is the group willing to trade-off issues of high priority interest?

Often managers tend to outline rules that hamper, or strangle the potential for creative options that are essential, in achieving the conditions listed above.

Two of the most common rules often imposed on a group is to apply the concept of either majority rule, or unanimous consent in making a decision. So, which one works best?

Although majority rule may work well in a cooperative group, it is less likely to work as well in a mixed motive group. It can be manipulated by one group to obtain a strategic advantage on another issue. Majority rule fails to take into account the preferences of all the parties, as each will attach different importance on different issues. It can also result in alliances, whereby one party makes a side deal with another. If you scratch my back on this issue, I will scratch your back on that issue.

It is suggested that unanimous decisions will in fact,augment the development of arriving at agreements that are more creative. This forces the group members to understand the issues, interests, and preferences of each party in detail. By exploring better ways to mix solutions, within the overall framework and by expanding your options, will better resolve the interests of all the representative groups.

Dealing with agendas

The general practice in how we approach our negotiation issues is usually accomplished through an agenda. We establish the order in how the issues will be discussed. Agendas are useful for either a competitive or a cooperative group. An agenda allows us to cover the material efficiently and effectively, in an orderly manner. Once an issue is dispensed with by the group, we normally don’t return to it.

However, an agenda works less efficiently in a mixed group of both cooperative and competitive elements, as they are less likely to arrive at creative solutions that address the needs of all the representative groups. Addressing many issues simultaneously, allows us to find solutions that are more effective. Once we can readily identify the priorities and interests of all the representative groups, we can develop a more complete and digestible solution package.

Coalitions

When you have more than two representative parties at the negotiations table, it is not unusual for two or more of the parties, to pool their collective resources or positions, to form a coalition. Coalitions have the potential to undermine the overall negotiations,by forming a power block to promote their own self-serving interests, to the disadvantage of the other parties.

This scenario may result in the majority rule theme discussed earlier, and we have already seen the drawbacks that can occur in this situation. Coalitions do not tend to use allocated resources wisely, in that they do not consider the needs and the objectives of the other members or the organization as a whole. This is another reason why unanimous consent, can be a more effective form of decision-making, as it negates the power of any coalitions that might wish to usurp the group as a whole.

Conclusion

Most groups who are represented at a negotiation, will generally consist of both cooperative and competitive elements, depending on the issues. Majority rule is less productive than unanimous consent. An agenda can be effective for a group that is either cooperative or competitive, but is less effective in a mixed group. Coalitions can be counterproductive but can be nullified, if unanimous consent is required. The complexities that group negotiations presents requires that your negotiation team be trained to successfully navigate their way to achieving your goals.

- Max H. Bazerman, Margaret A. Neale, ‘Negotiating Rationally’, The Free Press – MacMillian, (1992).

- J. Lewicki, A. Litterer, W.Minton, M. Sauders, ‘Negotiation’, 2nd Edition, Irwin,(1994).

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE