A New ICON for Negotiation Advice

Valuable advice to show how both parties can understand the criteria to find alternatives in achieving successful negotiations.

Finding Agreement in a Negotiation

Two decades after the original publication of Getting to YES, by Roger Fisher and William Ury, the conflict resolution classic is still unrivaled in providing a distinct prescriptive framework for turning rivals into collaborators (Fisher and Ury). Their method of principled negotiation remains one of the most powerful influences on the study and practice of negotiation within academia, government, civil society, and the business world (Susskind and Cruikshank).

Getting to YES provides a flexible prescription for improving social interaction. It empowers individuals with useful tools by changing conflict into opportunity. Individuals from all walks of life have learned to separate people from problems, focus on interests and not positions, use objective criteria to develop fair and satisfactory options for both sides, and to identify their best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA).

Getting to YES has been the basis of our professional mediation, facilitation and training work. Drawing on our experience, we will introduce the ICON teaching tool that our clients find useful for preparing for difficult negotiations.

Negotiation research and practice is necessarily multidisciplinary and diverse. An enormous literature has emerged from this field, and there are now numerous organisations dedicated to the resolution of conflict in accordance with the principles first set forth in Getting to YES. The clients we work with — business executives, companies, labor unions, and other groups — want to enhance their negotiation skills and come to us for prescriptive negotiation advice.

Prescriptive advice on mastering collaborative negotiation continues to be very relevant to people facing business, professional, and personal challenges. Both experimental studies and case studies suggest that people with collaborative negotiation training obtain better outcomes than those without such training (Bazerman & Neale, 112).

Our clients tell us they are tired of having to choose between caving in and sacrificing relationships in their most critical negotiations. And as users of negotiation advice grow in number and experience, the demand for simple, elegant and useful frameworks only increases.

To make a lasting impact on how our clients conduct business and resolve conflicts, our prescriptive advice must prove its worth in the real world, and in real negotiation situations. Many individuals and organisations we work with confront persistent, overt manipulation, and aggressive tactics. Moreover, constituent pressures and psychological barriers even further hinder their reaching their objectives (Arrow et al.; Kelman). In such contexts, parties find it difficult to accomplish negotiation tasks such as creating and distributing value. In the absence of negotiation expertise or facilitation, they are more likely to respond in kind to manipulative or hostile tactics, and this often leads to poor, lopsided outcomes, and damaged relationships.

Even when parties begin from a collaborative perspective, they are in danger of resigning themselves to “playing the game” according to a non-collaborative set of assumptions. As a consequence, manipulative and positional behaviours re-emerge. Clients increasingly approach us with the desire not to conduct business-as-usual. They claim they want win-win negotiation relationships in both their personal and professional lives. These two learning challenges — acquisition of critical skills, and ability to employ principled negotiation strategies, even when they are under attack or facing other barriers — help define our approach to teaching and consulting.

Participants must be able to quickly access relevant lessons and principles, and apply them appropriately. The quality of negotiation training – in particular the underlying pedagogy — is a key factor in the transfer of skills. A crucial challenge facing negotiation students is taking abstract negotiation concepts and applying them to real world problems (Gillespie, Thompson, Loewenstein and Gentner). In order to improve their negotiation skills, participants must be able put training and advice quickly into practice, and to learn from past negotiation experiences.

The ICON preparation tool achieves this task because it is accessible, and because our training methodology encourages participants to immediately apply ICON to their own negotiation challenges. Participants benefit from cases and simulations in which ICON is practised, and they make deeper connections to their own world immediately. By reducing the complexity of negotiation, we ensure more participants will continue to use the ICON framework and overcome barriers common to skills transfer.

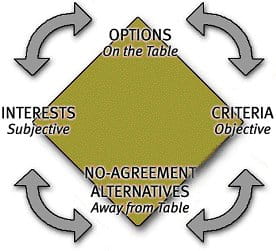

There is much more solid research on negotiation theory than there is digestible advice on negotiation practice. Many findings are only applicable within a single sub-field. Relatively little research is realised into educational or training frameworks. To solve this problem we set out to identify an uncomplicated, memorable, and effective negotiation learning device distilled from the broader array of practical and theoretical knowledge about negotiation. Beginning with Getting to YES, and using our extensive experience training skills, while facilitating complex disputes, we condensed a negotiation theory to its most basic and important elements. By focusing on four essential components; Interests, Criteria, Options, and No-agreement alternatives (or the ICON), we found a rigorous, useful preparation template. For negotiation teachers ICON works as a natural extension of Getting to YES and other user-friendly negotiation research of the past twenty years.

In our collective decades of consulting and training, ICON has been applied to numerous real life challenges. Here we recommend its use as a teaching tool for skills-based education or the educational component of a broader project.

How ICON Works

ICON can be explained best if laid out in a diamond with Interests in the west corner, Criteria in east corner, Options in the north corner, and No-agreement alternatives in the south corner. Each point of ICON relates directly to its adjacent points. For instance, individuals or parties who are about to engage in a negotiation have specific needs or Interests they want met and these may underlie the positions they come to the table demanding (Fisher, Ury & Patton; Lax & Sebenius,). The parties’ Interests will help them generate possible solutions, or Options, to resolving the dispute. Their Options can be further refined through the filter of neutral Criteria — objective standards or benchmarks. Their Interests may also help them to develop or strengthen No-agreement alternatives, or the steps each party will take if they do not reach agreement. A party can refer back to its Interests to assess the value and practicality of its No-agreement alternatives. Among its No-agreement alternatives a party will usually identify its best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), which serves both to alert and prepare each side for the consequences if no agreement is reached. While many experienced negotiation practitioners begin with Interests while thinking through a negotiation process, the four facets of ICON work in any order. For instance, a set of Criteria can help spark ideas for Options. Alternatively, a list of No-agreement alternatives may help a side clarify its Interests.

What Parties Want in Negotiation and Methods to Satisfy Those Desires

Getting to YES stressed the importance of recognizing what you want, and about taking an honest inventory of your underlying Interests when you engage in any negotiation. Arguably, these are your subjective Interests, tailor-made to your side given your situation, expectations, and experiences. Likewise, each side must anticipate and analyze the other side’s Interests in order to work out realistic Options.

Balanced against the Interests of each party are objective Criteria with which one can evaluate the fairness of demands. Examples of Criteria include market rates, past pay increases, and federal regulations. For instance, an agricultural workers’ union negotiating with farmers might depend on federal court decisions and EPA rules to argue for better safety equipment for its workers. Criteria are neutral precedents that both sides to a negotiation can use to develop and benchmark Options. In negotiations we want to see our objective needs met, and to know that the agreement is fair while being able to explain to stakeholders the key factors upon which decisions were based.

If Interests and Criteria help articulate what we desire, Options and No-agreement alternatives are proposals for concrete ways of getting it. We occasionally refer to Options that meet some or all of each party’s Interests as the on the table solutions, which are those Options we believe have some chance of meeting both parties’ Interests. When both sides contribute to putting Options on the table, this can lead to greater choice and creativity in coming to an agreement.

In many instances, the most influential factors that determine the outcome of a negotiation are the parties’ alternatives to a negotiated agreement. Parties are often significantly motivated to find common ground — or not to find common ground — by their knowledge of what will happen if no agreement is reached. A No-agreement alternative is an important baseline for both parties to evaluate the merits of various Options. Although No-agreement alternatives can be disappointing, they provide a crucial emergency stop to spiraling losses that can occur in negotiations. Armed with No-agreement alternatives, each side has well-defined indicators for when they should walk away from the table and a clear idea of what will happen if they do.

ICON is a catalyst for principled negotiations. It helps negotiators create and claim value by focusing on the substantive outcome of negotiations (Lax and Sebenius). While ICON provides the building blocks for collaboration, one still has to design and conduct a collaborative face-to-face negotiation. Deftly probing for Interests while using Criteria to understand and persuade rather than bully, and brainstorming for Options without the positional habit of focusing on only one option, we can identify No-agreement alternatives wisely. These are all skills that require relationship building and good communication. Once that communication is established, ICON is meant to be used as a tool for decision-making — like conducting a cost-benefit analysis — for tackling fundamental choices that arise.

ICON in Practice

ICON’s simplicity and logic are best demonstrated through action. In our mediation work we first ask parties to apply the four elements of ICON within their partisan teams, and then jointly with the other side as the process advances. The success of this approach was particularly well demonstrated during a collective bargaining negotiation we facilitated in 1998 between the San Diego School District and the San Diego Teachers Association (Lum and Christie).

For each major issue the parties separately analysed their Interests, Criteria, and Options. For the negotiation as a whole and on selected issues, the parties also evaluated their own and the other party’s No-agreement alternatives. Mapping out ICON, and then sharing the information in a principled fashion, aided the parties to move through the issues quickly. They were able to identify creative options that met their interests, and a teachers’ strike or a return to school without a contract was averted.

Among the most problematic issues facing the San Diego School District (aside from typical disputes over salaries and benefits) were inadequately prepared students, limited resources, and poor teacher support in its inner city schools. The bulk of teachers who found an opportunity to transfer out of the inner city did so, leaving these schools with a constant influx of inexperienced teachers. Staff at some of the inner city schools had an average of three years teaching experience or less. We asked both sides to the negotiation to work through ICON as part of the mediation process. The following is a summary of their findings.

What were the Teachers’ subjective Interests? The teachers wanted as much control over their own work lives as possible, and for their tenure and experience to be valued by the San Diego School District. They desired improvement in the inner city schools and felt that providing new teachers with mentoring and coaching would help achieve this aim.

What were the District’s subjective Interests? The District administration wanted as much staffing discretion as possible to make the most appropriate matches between teachers and students. It also wanted a balance of newer teachers and experienced teachers at each school site.

What were other parties’ interests? Students and parents wanted high quality education. The business community, which contributed financial support, desired quantifiable evidence that the schools as a whole were improving. Organised parent groups were specifically concerned with the troubled schools in the inner city.

What were the objective Criteria? The current contract had specific transfer policies that allowed teachers with more years of tenure to have the first option to transfer to other schools. Other districts had different standards about how many years of tenure were required before one could transfer. Also, other school districts had different voluntary and involuntary transfer policies. Some districts offered stipends for taking on the added responsibilities associated with mentoring. There were charter schools within the San Diego School District that suspended union regulations. Some school districts in the country were turning over their difficult schools to private education companies.

What were some possible Options to put on the table? Among them were longer waiting periods before initial transfers could occur; mandatory rotation for experienced teachers at challenging schools; mentor stipends for teachers at designated schools; or continuation of the status quo.

What were the teachers’ No-agreement alternatives? If teachers weren’t able to reach specific agreements with the administration regarding the inner city schools, the union could provide unilateral support to teachers in the most challenged schools and/or file grievances on behalf of individual teachers. If the overall negotiations were to fail, teachers could take strike action; “work to rule” (performing only those duties stipulated in the contract and nothing more); conduct before-and-after school pickets; conduct a media campaign to persuade the public of the teachers’ cause; or refuse to negotiate for a specific period of time.

What were the District’s No-agreement alternatives? The District administration could reject reaching an agreement on the inner city schools and instead place them on probation and/or look for outside foundation funding to make the needed improvements. If the overall negotiations were to fail, the administration could prepare strike plans; lockout teachers; or refuse to negotiate for a specified period of time.

Returning to the ICON diamond, you can see how each point impacts the other three. In the case of the San Diego School District, because it was revealed that increasing achievement in the most challenged schools was a very strongly shared interest, it became easier to propose Options to meet both sides’ needs. Moreover, both sides felt Criteria that included data from other school districts that either increased or decreased achievement was both credible and persuasive. The No-agreement alternatives were designed based upon the parties finding unilateral ways to meet their interests (e.g. the administration unilaterally looking for funding).

The parties struggled with the inner city school problem. The union was firm about preserving teachers’ rights and freedoms, which meant that Options calling for mandatory rotation or increasing years prior to transfer were non-starters. Both parties began to look together at mentor stipends. Initially, the union wanted stipends for all teachers who provided mentoring. However, given the budget constraints, both parties doubted the stipend amount would be sufficient to appeal to teachers. The idea of focusing all the mentor budget dollars on the most challenging schools was initially rejected because individuals on both sides were concerned about not treating all schools equally. After further discussion about their Interests, consensus grew that a primary goal for everyone was to improve the most challenged schools. The parties were then able to agree to a targeted mentor stipend that would be adequate to attract experienced teachers to those inner city schools that most needed help.

Training Participants in a Principled Negotiation Approach

ICON provides individuals with the ability to think strategically about negotiation, and making choices and decisions proactively while continually building collaborative working relationships. Our teaching, training and consulting helps move negotiators quickly from reflection to action. One critical practice session in our negotiation training involves helping participants create their “ICON dialog“ skills. Participants practice forming statements that fit each of these four elements. The practice of ICON is actually accomplished by having students and participants script out their most challenging negotiation conversations and replay them with co-participants who have been prepared to coach one another.

Whether our clients are high-level corporate executives, union-management negotiators, or graduate students, they find it difficult to escape a common dilemma: often the words they use in negotiations don’t have the impact they intend. The wrong language can lead to poor results and can hurt working relationships. It is difficult to deliver a hard message. (Stone, Patton and Heen) We all have faced the challenge of crafting a message that communicates our desire to satisfy legitimate needs while also seeking to build a key relationship.

While several negotiation training methods focus on tactics meant to provide advantage to one side, engaging in an “ICON dialog“ allows negotiators to have a broad range of responses in any negotiation situation. This enables participants to learn and practice the skill of principled negotiation in a training session.

Once participants are skilled at “ICON dialog“, we teach them strategies for persuading the other party to adopt a principled negotiation approach. Being able to put the ICON elements into play requires dialog about how the parties will negotiate with each other and what options they can make about the negotiation process.

Conclusion

ICON is easy to understand and to implement. Our clients report to us that they use ICON for the mundane as well as the exceptional negotiations in their lives. We have found that ICON frees experienced and novice negotiators alike from becoming bogged down in process problems. They are better able to devote their energies to coming up with imaginative and practical solutions. ICON has worked for business people, parents, tenants, job seekers — in fact, it is for everyone.

ICON was originally conceived as a learning tool for concisely conveying the key components to wise decision-making in negotiations. Participants often report that ICON is the most memorable aspect of their training on negotiation and one that permitted them to think strategically about negotiation choices. For them, ICON made principled negotiation an accessible and practical alternative to many conflict situations in both their professional and personal lives.

Grande Lum is a founding principal of ThoughtBridge, LLC, a consulting firm. Anthony Wanis-St. John is on the full-time faculty at Seton Hall University’s School of Diplomacy and International Relations.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE