Negotiator Styles in Bargaining

This article covers the problem of the interactions of opponents with different negotiation styles. Discusses effective tactics to gain positive results.

I. INTRODUCTION

Attorneys and business people negotiate perpetually. They negotiate within their own organizations, with prospective and current clients and customers, and with other parties. Most negotiators employ relatively “cooperative” or relatively “competitive” negotiation styles. Cooperative bargainers tend to behave more pleasantly, and they endeavor to generate mutually beneficial agreements. Competitive bargainers are often less pleasant, and they work to obtain optimal results for their own sides. Most people look forward to interactions with cooperative opponents, but frequently dread their encounters with competitive negotiation adversaries.

Negotiator styles significantly influence bargaining interactions. Which styles are used by more negotiators? Which styles are associated with more proficient negotiators and with less effective bargainers?

II. COOPERATIVE/PROBLEM-SOLVING AND COMPETITIVE/ADVERSARIAL STYLES

Most negotiation books divide bargainers into two stylistic groups: (1) Cooperative/ Problem-Solvers and (2) Competitive/Adversarials. Cooperative/Problem-Solving negotiators move psychologically toward their opponents, try to maximize the joint returns obtained by the bargaining parties, look for reasonable results, begin with realistic opening positions, behave in a polite and sincere manner, rely upon objective standards to guide discussions, rarely resort to threats, maximize the disclosure of relevant information, are open and trusting, work meticulously to satisfy the underlying interests of themselves and their opponents, are prepared to make unilateral concessions, and attempt to reason with people on the other side. Competitive/Adversarial negotiators move psychologically against their opponents, try to maximize their own returns, strive for extreme results, begin with less realistic opening offers, behave in an adversarial and insincere manner, focus mainly on their own positions rather than rely on objective standards, frequently resort to threats, minimize the disclosure of their own information, are closed and untrusting, endeavor to satisfy the interests of their own side, try to make minimal concessions, and manipulate opponents.

Cooperative/Problem-Solvers readily disclose their critical information, explore the underlying interests of the respective parties, and seek results that maximize the return to both sides. They often consider alternatives that may enable the bargainers to increase the overall pie through trade-offs that simultaneously advance the interests of both sides. For example, when money is involved, they may agree to future payments or in-kind payments that realize the underlying interests of the different participants. Competitive/Adversarials engage in disingenuous games-playing. They cloak their negative information, and try to manipulate opponents into providing them deals that maximize the returns for themselves. They may even ignore alternative formulations that might benefit their opponents if those alternatives do not clearly advance their own interests.

In the early 1980s, Gerald Williams performed a study among attorneys in Phoenix and Denver to determine what percentage of legal negotiators behaves in a Cooperative/Problem-Solving and a Competitive/Adversarial manner [Williams, Legal Negotiation and Settlement (1983)]. He discovered that lawyers considered 65 percent of their colleagues to be Cooperative/Problem-Solvers, 24 percent to be Competitive/Adversarials, and 11 percent to be unclassifiable.

III. COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF COOPERATIVE/PROBLEM-SOLVING AND COMPETITIVE/ADVERSARIAL NEGOTIATORS

When I ask Effective Legal Negotiation course participants to describe the styles of effective negotiators, they usually suggest they are aggressive persons who openly indicate a desire to obtain better results for themselves than they provide their opponents. They often suggest that these advocates may use discourteous behavior to intimidate weaker opponents. I then ask these respondents what they would do if someone came to their office that afternoon, openly indicated that they were there to clean them out, and exacerbated the situation with some gratuitous insults. Would they think that someone has to lose and it might as well be themselves — or would they get up for the interaction to avoid exploitation by such a manipulative adversary? They laugh when they realize how rapidly they would change their own demeanor to avoid exploitation. They indicate that they would be reluctant to disclose their critical information, lest their opponents take advantage of their one-sided openness. They also suggest that they would use more strategic tactics designed to neutralize the competitive behavior of their adversary.

I then ask them how they would respond to someone who came to their office, and politely indicated an interest in achieving mutually agreeable terms that would meet the underlying interests of both sides. They usually suggest that they would respond in an open and cooperative manner designed to maximize the joint results achieved. By this point, they start to appreciate how much easier it is to obtain beneficial negotiation results from others when people act in an open and apparently cooperative fashion. They also recognize how much more difficult it is for openly Competitive/Adversarial bargainers to achieve their one-sided objectives.

Gerald Williams asked the respondents in his study to classify opponents as “effective,” “average,” and “ineffective” negotiators. They suggested that while 59 percent of Cooperative/Problem-Solvers were “effective” negotiators, only 25 percent of Competitive/ Adversarials were so adept. On the other hand, while only 3 percent of Cooperative/ Problem-Solvers were thought to be “ineffective” negotiators, 33 percent of Competitive/ Adversarials bargainers were placed in that category.

In the late 1990s, Andrea Kupfer Schnedier duplicated the Gerald Williams study utilizing attorneys in Milwaukee and Chicago as her data base. Her findings reflect changes that have influenced our society in general over the past two decades. People are less pleasant to one another today than they were twenty years ago. Many persons have become increasingly impatient and less polite [Schneider, “Shattering Negotiation Myths,” 7 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 143 (2002)].

I would expect the less courteous and more repugnant Competitive/Adversarial negotiators described in Professor Schneider’s study to be not as effective than the less negatively described Competitive/Adversarial bargainers in the Williams study, and this is precisely what Professor Schneider found. While Professor Williams found 25 percent of Competitive/ Adversarial negotiators to be “effective,” Professor Schneider found only 9 percent of such bargainers to be “effective.” This change should be contrasted with the relatively slight decrease in the percentage of Cooperative/Problem-Solvers considered to be “effective” negotiators from 59 percent in the Williams study to 54 percent in the Schneider study.

The findings with respect to persons considered “ineffective” negotiators are starker. Professor Schneider found almost no change in the tiny percentage of Cooperative/Problem-Solvers considered “ineffective” bargainers, but she found a profound change with respect to the percentage of Competitive/Adversarials considered “ineffective” negotiators — increasing from 33 percent in the Williams study to 53 percent in her own study. This increase in perceived ineptitude among Competitive/Adversarial negotiators would most likely be attributable to their expressed competitiveness and more unpleasant demeanor.

In the thirty years I have taught Legal Negotiating courses, I have not found proficient Cooperative/Problem-Solvers to be less effective than proficient Competitive/Adversarials. The notion that a person must be uncooperative, selfish, manipulative, and even abrasive to be successful is wrong. To obtain beneficial negotiation results one need only possess the ability to say “no” forcefully and credibly to convince opponents they must increase their offers if agreements are to be achieved. They can accomplish this objective courteously and quietly, and be as effective as those who do so more demonstrably.

I have only noticed three significant differences regarding the outcomes achieved by different style negotiators on my course exercises. First, if a truly extreme agreement is obtained, the prevailing party is usually a Competitive/Adversarial negotiator. Since Cooperative/Problem-Solving bargainers tend to be more fair-minded, they usually refuse to take unconscionable advantage of inept or weak opponents. Second, Competitive/Adversarial advocates generate more non settlements than their Cooperative/Problem-Solving cohorts because of their extreme negotiation positions and frequent use of manipulative and disruptive tactics. Third, Cooperative/Problem-Solving negotiators tend to accomplish more efficient combined results than their Competitive/Adversarial colleagues — i.e., they tend to maximize the joint return to the parties.

IV. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN PERSONS WITH DIFFERENT NEGOTIATING STYLES

When Cooperative/Problem-Solving bargainers interact with other Cooperative/Problem-Solvers, their encounters are generally cooperative. The participants are relatively flexible with their critical information, and they seek to achieve terms that maximize the joint return of the parties. Interactions between Competitive/Adversarial negotiators are usually competitive, with minimal information disclosure and the use of manipulative tactics to advance each side’s own interests.

When Cooperative/Problem-Solvers negotiate with Competitive/Adversarials, their transactions lean towards more competitive than cooperative. If Cooperative/Problem-Solvers are naively open with less forthcoming Competitive/Adversarials, information imbalances develop which favor the more strategic Competitive/Adversarials. As a consequence, Cooperative/Problem-Solving participants must use a more competitive approach to avoid exploitation. These cross-style interactions generate less efficient agreements than encounters involving only Cooperative/Problem-Solvers, and they increase the likelihood of a non settlement.

V. THE COMPETITIVE/PROBLEM-SOLVING APPROACH

In their studies, Professors Williams and Schneider discovered that certain traits are shared by both effective Cooperative/Problem-Solving negotiators and effective Competitive/Adversarial bargainers. Successful negotiators from both groups are thoroughly prepared, are perceptive readers of others, and wish to maximize their own client’s return. Since client maximization is the quintessential characteristic of Competitive/Adversarial negotiators, this common trait would imply that many effective negotiators who are identified by their colleagues as Cooperative/Problem-Solvers are really wolves in sheepskin. They exude a cooperative style, but seek competitive objectives.

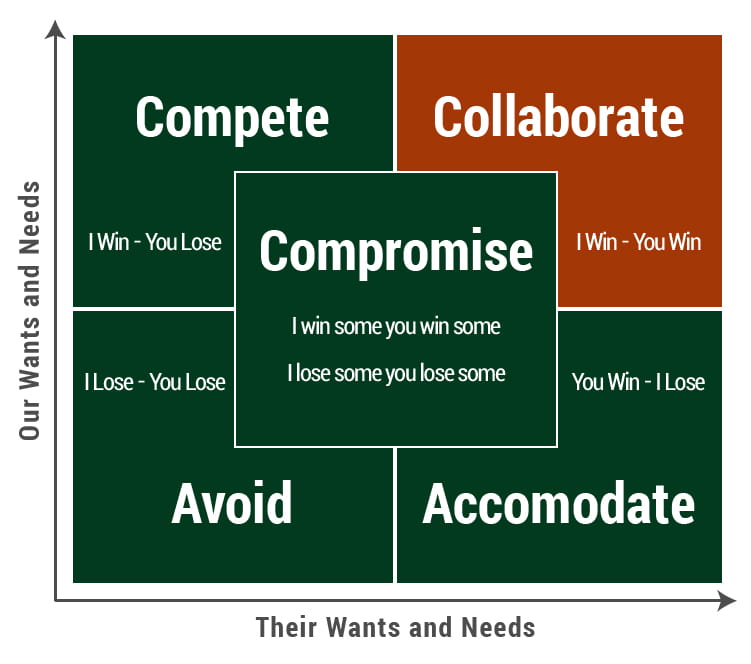

Most successful negotiators join the most salient traits associated with the Cooperative/Problem-Solving and the Competitive/Adversarial styles. They seek to maximize client returns, but strive to achieve this objective in a congenial and seemingly ingenuous manner. Unlike less proficient negotiators who regard bargaining encounters as “fixed pie” win-lose endeavours, effective bargainers realize that in multi-item interactions the parties value the various terms differently. They may try to claim more of the distributive items desired by both sides, but they also seek shared values. They recognize that by maximizing the joint returns, they are more likely to maximize the settlements achieved for their own clients.

Despite the fact that effective bargainers generally aspire to attain as much as they can for themselves, they are not “win-lose” negotiators. They never judge their own success by asking how poorly their opponents have done. They recognize that the imposition of bad terms on their adversaries does not necessarily benefit themselves. All other factors being equal, they endeavor to maximize opponent satisfaction. They realize that if they are pleased with what they obtained, they have had successful encounters — even if their opponents are equally satisfied.

Proficient negotiators do not seek to maximize opponent returns for purely altruistic reasons. This approach effectively permits them to advance their own interests. First, they have to provide adversaries with sufficiently generous terms to entice them to accept agreements. Second, they want to be sure opponents will honor the deals agreed upon. If they experience post-agreement “buyer’s remorse,” they may try to get out of the deal. Finally, they acknowledge the likelihood they will encounter their adversaries in the future. If those persons remember them pleasantly as courteous and professional negotiators, their future bargaining interactions are likely to be successful.

Effective Cooperative/Problem-Solvers and effective Competitive/Adversarials understand that people tend to work most diligently to accomplish the needs of opponents they like personally. Overtly Competitive/Adversarial bargainers are rarely perceived as likable. They exude competition and manipulation, and they generate likewise responses from opponents. Seemingly cooperative negotiators, however, seem to seek results that benefit both sides. Since others enjoy interacting with them, these individuals find it easier to induce unsuspecting opponents to lower their guard and make greater concessions.

Over the past several decades, lawyers and business people have become less polite toward one another. Many have become more win-lose oriented. They seem to fear that if their opponents obtain what they want, they will be unable to achieve their own goals. Negotiators who encounter rudeness from opponents should recognize that such inappropriate behavior is not a sign of negotiator proficiency, but just the contrary. Uncivilized behavior is a substitute for bargaining competence. Skilled negotiators do not utilize offensive conduct. They recognize that such behavior is unlikely to induce adversaries to give them what they desire.

Another critical reason for behaving professionally during bargaining encounters pertains to recent studies suggesting that people who commence negotiations in positive moods bargain more cooperatively, while individuals who begin in negative moods bargain more adversarial. As a result, negotiator pairs who commence bargaining interactions with positive moods achieve larger joint gains than negotiator pairs who begin with negative moods.

Charles Craver is a Professor of Law, GeorgeWashington

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE