How NOT to Negotiate in China

This case study demonstrates how not to negotiate a business contract in China.

Overview

In 1998 Simon Turner worked for Bassano, a large Australian women’s wear company with eighteen retail outlets across Australia. The following story recounts his experience in a business negotiation in Beijing with Happy Clothing.

Bassano required a cheaper manufacturer of tailored women’s wear and approached Happy Clothing, a tailored menswear manufacturer, to provide this service. Turner and his CEO Brian Thompson traveled to Beijing with a Chinese-Australian employee, Zhu Yi, who would act as interpreter.

While Turner went as the product specialist, management thought his previous experience working in India would be valuable. Turner, however, was not confident that this provided him with the necessary skills to negotiate in China. He had worked in high-context societies but was unfamiliar with Chinese culture. He thus decided to adopt a few of the basic approaches he had used in India, namely, being patient, extremely polite, and fastidious when it came to details.

The Scene

Thompson felt he had to finalize the negotiation in two days. Turner tried hard to convince him that more time might be required, but Thompson only added one day to their stay, assuring Turner: “I’m good at this, just watch and learn.” Fully believing only two days would be needed, Thompson also scheduled other meetings for the three-day visit. Sadly Thompson lacked the business skills and the advanced business negotiation capability necessary to conclude deals in China.

On day one, Thompson and Turner met Liu Baoping, Zhang Hua Ai, and Ping Ming. Liu spoke reasonable English, but the other two spoke no English. The morning was spent drinking tea, with discussion focused on Happy Clothing’s capability. Thompson attempted to turn the conversation to Bassano’s requirements, but the Chinese negotiation team did not seem interested. Soon after, the Australian team was ushered to lunch, followed by a ninety-minute drive to the company’s factory. After an impressive and thorough tour of the facilities, they were driven back to central Beijing for a 5 P.M. banquet dinner. The timing seemed peculiar to Thompson and increased his frustration with the day’s proceedings.

Negotiations Commence

Discussion began next morning. The Chinese knew a lot about Bassano and its competitors, which impressed Turner immensely, as he had not come across this approach in India. It also increased his confidence about Happy Clothing’s ability to meet their needs.

The Chinese team confirmed they could meet Bassano’s volume and price requirements. The deal meant that Bassano’s landed cost for a fully tailored women’s suit was $20. The retail price of $150 meant potentially high profits.

However, a problem arose when Happy Clothing identified its terms of trade. It was keen to maximize its foreign currency holdings, as this would lead to concessions from the government vis-à-vis control of their business. For this reason, the contract was conditional on Bassano managing distribution of Happy Clothing menswear in Australia. Thompson refused, but the Chinese remained firm that no deal could be negotiated otherwise.

A Gift Horse

Turner, meanwhile, believed their warehouse could easily accommodate more stock. He saw an opportunity to increase sales and profits by distributing this product or, as an alternative, the opportunity to subcontract the distribution to another company and make a profit as middleman. Thompson remained indignant and so did the Chinese.

Turner, however, encouraged Thompson to consider this option and to calculate the gains of both $20 women’s suits and the subcontracting of distribution, together with the option of continuing to manufacture suits in Australia. Eventually Thompson consented—as long as the cost of the suits made the venture feasible.

Although Yi had said nothing on day one, at lunch on day two she told Turner that she thought the negotiation was going well: “I think they like you but I don’t think they like Thompson.” The afternoon session became more focused on the Happy Clothing rather than the Bassano contract, further infuriating Thompson, who made no attempt to disguise his feelings.

Knowing that the negotiation would take three days, Turner decided to provide Happy Clothing with information on required sizes and fabric considerations for an Australian market before moving on to what Bassano required. The Chinese were very pleased with this.

At the end of day two, Turner felt confident that a deal would be struck. But Thompson believed that only Happy Clothing would benefit, by gaining access to the Australian menswear market. As Thompson had another meeting on day three and possibly would not be able to attend the final stage of the negotiation, he provided Turner with the required agreement conditions that included the terms for a written contract.

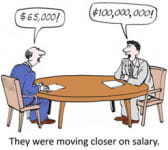

The talks on the third day were slow. Turner was able to negotiate a price on Happy Clothing’s menswear that would allow healthy profits for Bassano, even were it to subcontract the distribution to another company.

Bassano’s contract was more difficult, however, not because of price or volume requirements, but because the contract was to include payment penalties applicable were certain terms not met. The Chinese told Turner that, not being usual practice, this would be difficult to accept. They gave Turner their word that they would meet his requirements, but he told them that he was not able to negotiate a contract minus those penalty stipulations.

So Close, Yet So Far

Thompson was able to return to the negotiation, and he exploded when Turner told him that they were having a problem with the written contract. Standing up, Thompson pointed at Liu and said with heated emotion: “Now, listen, I’ve been waiting three days for a yes or no answer and we keep going around the block, giving more to you as we go. We leave tomorrow and want your commitment now. No more negotiation. If you can’t do it then we’ll find someone else; there are millions of people like you here, and if you don’t deliver we’ll piss you off and find someone else. It’s as simple as that. Just let us know: yes or no.”

Turner looked at the Chinese and knew the negotiation was over. Their expressions had become stern and cold; Liu left the room and the other two Chinese talked together quietly. Liu returned about twenty minutes later and said: “We will have to consider this. We cannot make a decision now.” Meaning: NO DEAL! The Chinese then packed up their things, said goodbye, and left the room. Turner’s comment to Thompson was: “You blew it, mate.”

A week after returning to Australia, Thompson realised the offer of Happy Clothing distribution would be a good opportunity after all and decided to contact Liu. Turner asked Thompson not to do so, saying that he would contact Liu, as he had established a good relationship with him. Thompson refused his offer, determined to salvage the situation himself.

The Chinese response was: “We are not able to do business with you at this time.” A further approach, two months later, met with the same reply. Three months after his visit to China, Turner left Bassano, which was then looking in South Korea for an alternative manufacturing base.

Commentary

The problems with this negotiation stemmed initially from Thompson’s ethnocentric views, with no clue about giving face in China. Assuming that the pace of the negotiation would be the same as at home, he failed to recognize that the Chinese needed to spend a day establishing a relationship. He was not prepared to deviate from the expected because of the Chinese company’s desire for negotiating for more foreign currency. Further, he saw the Chinese reluctance to commit to a formal contract as an effort to weight it in their favor.

The Chinese behaved like Confucian gentleman, but Thompson showed them no respect. They offered a win-win contract, but Thompson dismissed it.

The case highlights the need for negotiators who can get along with the Chinese and for preparation before negotiating with the Chinese. Thompson was the wrong person to deal with the Chinese, and Turner was the right one.

In terms of preparation, Thompson lacked understanding of the economic structure and the close connection of companies to the government, knowledge of the potential negotiating styles, respect for the Chinese emphasis on trusting negotiation relationships, and their aversion to contracts. Bassano could have agreed verbally that the distributorship of Happy Clothing menswear was conditional on Happy Clothing meeting the standards required by Bassano for their women’s wear. This would have provided the motivation needed for Happy Clothing to meet the Bassano production quality and schedules.

Although Thompson was afraid of being tricked by the Chinese and convinced that he could bully them into a deceit – and trick-free agreement, his cowboy tactics were anathema to the Chinese.

This negotiation case is published with permission from Dr Bob March’s excellent book “Chinese Negotiator”.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE